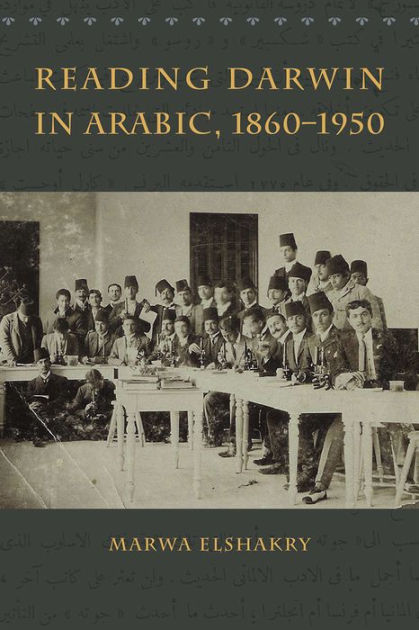

In his 1887 autobiography, Charles Darwin was astonished by the discussions surrounding his book On the Origin of Species in places as far-flung as Japan, and even saw an article written in Hebrew explaining that “the theory is in the Torah!” Marwa Elshakry, the Egyptian researcher, cites this excerpt from Darwin’s biography at the beginning of her book Reading Darwin in Arabic Thought, 1860-1950. She does this to indicate the extent of the global spread of Darwin’s ideas about evolution. However, she also does this to point to an important dimension that she was busy tracking in the Arab world in her book. This dimension is researching every culture about the origins of the ideas of evolution in its local ideology. If there were Jews who claimed the existence of the theory in the Torah, then there are Muslim scholars and thinkers who attributed the ideas of the theory of evolution to the Qur’an and the Islamic heritage.

When the author developed this work, which is the culmination of a long research project that spanned more than 10 years, during which she published many related papers, she aimed to study several aspects of how Arabs received Darwin’s ideas at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. I explored how Darwin’s work was received in the Arab world. This investigation covered varying levels of circulation. It examined the knowledge of the theory and its origins. It also considered the diverse frames of reference for these many interpretations. I also explored how the different social, political, and intellectual contexts influenced the reception of the ideas of ascent and evolution. This included considering applications that even Darwin himself had not previously envisioned for the transfer of his ideas. The author also aimed to trace the network of meanings that emerged from Darwin’s readings as a part of it and not a measure of it, and to observe the creative tension in the circulation of meaning in different languages and places, by studying how the Arabs translated the terms of evolution.

The Author’s Path to this Work

First, when we examine the biography of the author and the development of her research interests leading up to the writing and publication of this book in 2013, we find the following. After her graduate studies at Princeton University, Marwa Elshakry turned her attention to the histories of science, technology, and medicine in the modern Middle East. She also explored the relationships of these fields with religion and culture within the imperial context of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries In 2003, Elshakry’s doctoral thesis, titled “Darwin’s Legacy in the Arab East: Science, Religion, and Politics, 1870-1914,” charts how Darwinian ideas emerged as a popular and controversial topic in the Arab world in the late Ottoman Empire and in the period of Western colonialism and missionaries. It explores the ways in which ideas of evolution have helped shape debates about the relationships between science and religion and the emergence of new trends in civilizational progress and social development. Later in 2006, while she was working as an assistant professor in the history of science at Harvard University, Elshakry received a Carnegie grant to work on a research project entitled: “Science and Secularism in the Arab World after Darwin.” This project included publishing a book – and it is this book that we are reviewing – and a collection of scientific articles for the masses. During this project, Elshakry attempted to address three main questions: How did the translation of modern concep ts of science reshape the cognitive and social fields in the Arab world? What are the responses to Darwin’s ideas about the relationship of religion and science, and how do they help us understand concepts of secularism in this region? Finally, how has the discussion of science and development changed Muslim thinkers’ perceptions of Arab society and politics in the recent past?

In 2009, Marwa Elshakry published an article in Nature journal, one of a collection of articles published by the popular magazine about the global response to Darwin’s ideas. Elshakry’s article was titled “The Global Darwin: Eastern Enchantment,” in which she explained how people from Egypt to Japan used Darwin’s ideas to reinvent their fundamental philosophies and religions. During and after that, she published a collection of articles related to the chapters of her upcoming book. In 2008, she published an article entitled: “Knowledge in Motion: The Cultural Politics of Modern Science Translations in Arabic” about the problem of the global mobility of modern scientific knowledge by looking at scientific translations in modern Arabic, and an article entitled: “The Exegesis of Science in Twentieth Century Arabic Interpretations of the Qur’an,” then in 2010, “Darwinian Conversions: Science and Translation in Egypt and the Levant.” In 2011, she addressed the issue of the connection between the dissemination of science in its modern sense and Protestant missions in an article titled “The Gospel of Science and American Evangelism in Late Ottoman Beirut.” In all of these research works, Elshakry was developing the topics of the book that will be published in 2013, whether in the formation of the concept of science in the modern sense in the nineteenth century, or how the Arabs received scientific theories within their own debates. However, we notice a decline in the presence of the topic of secularism in the recent works that culminated in the book compared to the earlier exploratory works.

******

Through its seven chapters, Elshakry goes through different points in time in her book, each of which has a prominent figure who represented an expressive shift in the paths taken by the theory of evolution and other modern scientific theories in the courses and discussions of the Arab world. Here we present some of the basic topics that were a common factor that Elshakry’s thesis focused on in the various stages it was exposed to, while trying to quickly point out discussions that took place in Arab thought for the same topics that the author did not refer to.

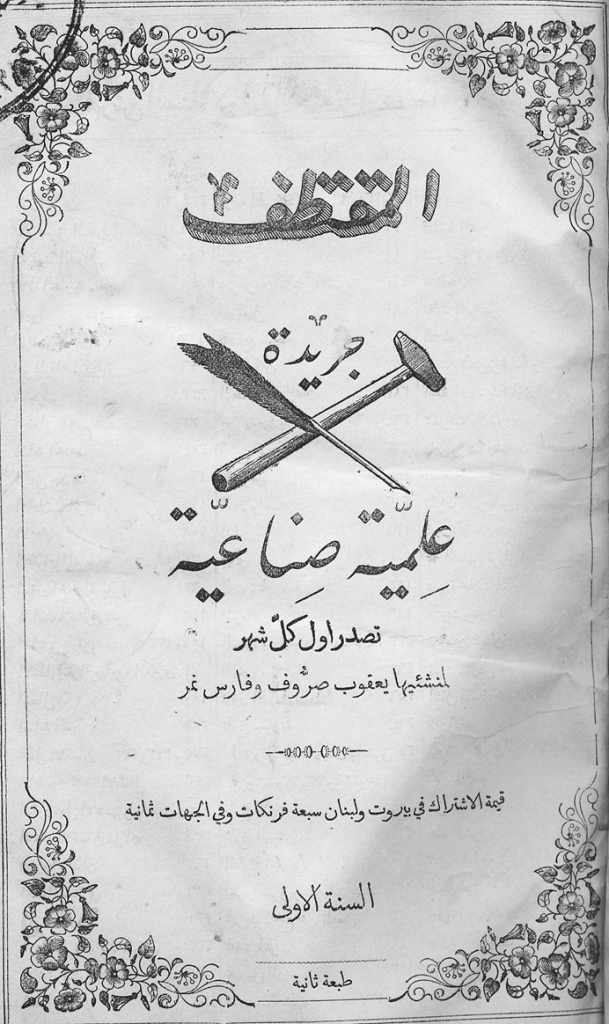

Print and the Community of New Readers

The author explains how the emergence of scientific journals that contributed to the spread of Darwinism, such as Al-Muqtataf, Al-Hilal, and others, was behind the rapid spread of Arabic printing culture in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Muhammad Ali established the Bulaq Press in the first half of the nineteenth century, which printed approximately 81 translated books on science, in consequence, new groups of Arab readers appeared during the reign of Muhammad Ali. In the second half of the nineteenth century, there was a real expansion in the Arab press, which the author goes on to detail, highlighting how the press in Cairo, Beirut, and the major urban centers in the Arab world laid the foundations for a new community of Arabic readers. Elshakry believes that the publication of Al-Muqtataf (1876) sparked the interest of Arab readers in popular scientific writings, noting the size of this community of readers who followed scientific journals and even corresponded with them with articles discussing the new theories and scientific discoveries they presented. This interest in receiving modern sciences necessitated innovation in terminology and the introduction of a huge amount of modern scientific terms into the Arabic language. When the author presents the career of Sheikh Muhammad Abduh, she draws a conclusion from it. The great development of an Azhari sheikh, who addressed the issues of his time and confronted what the new sciences put forward, such as the theory of evolution and other challenges to religious heritage, owed greatly to the emergence of new media and institutions. These included newspapers, publishing houses, schools, modern libraries, and salons. The Sheikh’s ideas were formed within these scientific and literary platforms, and they had a great impact on his writings. Also, the significant increase in the percentage of educated people among the new middle classes living in cities was a reason for the growth in the number of newspaper readers. As a result, the number of copies sold of all Arabic newspapers in Egypt increased from 180,000 copies in 1929 to more than half a million copies two decades later. This growing audience was one on which Salama Moussa left his mark. Salama Moussa is one of the most important publishers of the theory of evolution in Egypt and the Arab world.

What the author did not mention about this new environment was noted by another student of hers, Fathi Al-Miskini. The printing press is “securing a pattern of free public communication between minds that the people of old did not know,” that is, the event of enlightenment, in that it is, as Kant says, “a public use of reason.” This free public communication between minds that learn and think made it possible to escape from the influence of a religious authority ruling the acculturation process and receive modern sciences. It even made it possible to discuss this authority, as happened between Muhammad Abduh, Farah Antun, and others.

Science as a Global Phenomenon

Another factor, Elshakry explains, played a fundamental role in the way Arabs received the theory of evolution and other new scientific theories, which is science gaining a new meaning, whether in the global context, when science appeared in the nineteenth century as a global phenomenon, or in Arab contexts when the concept of the word “scientist” changed. The rapid spread of new media, such as magazines, newspapers, and printed books, enabled the emergence of a new class. This class consisted of educated people, intellectuals, technocrats, and writers. Additionally, the rise of new civil institutions and schools that transcended traditional religious groups and circles controlled by the sheikhdom also contributed to this development. As Elshakry states, “they established the methods, vocabulary, and rules that are now known as science.”

Here, that is, with regard to the dissemination of new sciences and science assuming a new meaning and a different status than before, the author gives an important role to Al-Muqtataf magazine in particular, and to its editors, Yaqoub Sarrouf and Fares Nimr, who are teachers at the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut, now the American University. This magazine, which had a long history in the Arab world, and whose issues reached many Arab countries, was destined, according to Elshakry, to play an important and vital role in disseminating Darwin’s ideas. The author reviews the circumstances of the emergence of Al-Muqtataf magazine and the conditions that Sarrouf and Nimr went through, whether in Beirut or in Egypt after they were forced to move there. The story of Al-Muqtataf, its role in disseminating evolutionary ideas, and the debates it has sparked, becomes central to several of the book’s seven chapters, and perhaps this space devoted to the excerpt is relatively overstated. This digression into the story of the magazine and its editors intensified the narrative pattern that characterizes many of the chapters of Elshakry’s book.

The author explains how Sarrouf and Nimr formed, by the end of the 1870s, a new reading society in some Arab countries, a society that adhered to science as a field full of possibilities for radical change. Science became for them the solution to the problem of progress. We point out here that this type of societies that believe in science as an essential bridge to progress is what Abdullah Laroui addressed in Contemporary Arab Ideology, represented by the character of Salama Moussa, to whom the author refers to, to dedicate part of the sixth chapter in her book.

Evolutionary Conditioning

During a 2009 interview with Marwa Elshakry on the Nature journal podcast, she discussed her project revolving around how Darwinism was received in the Arab world. Elshakry pointed out that many people today view Darwinism as a doctrine that opposes religion or theology. She noted, however, that this sentiment was not prevalent at the end of the nineteenth century. In fact, many cultures even adapted ideas of evolution into their own beliefs about the origin of the universe and creation. The idea of different cultures adapting Darwinism to their own traditions and philosophies is an important one. It articulates with many aspects of the Arab reception of the theory of evolution that Elshakry addressed in her book. For example, she discussed the position on religion held by pioneers in spreading the theory, such as Al-Muqtataf and Shibli Shumayyil. She also examined how the theory of evolution reformed Islamic reformism, as seen in the work of figures like Al-Afghani, Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida, who viewed it as harmonious with Islamic texts. Elshakry even explored the translation methods used by Ismail Mazhar, the most important translator of The Origin of Species, in conveying the ideas and terminology of evolution. She believes that one of the main reasons for the international fame of Darwin’s ideas is the ease of imitating them in the origins of local thought, “whether it is theological, moral, or cosmological thought.”

The author recounts how the debate was sparked in the Arab world about the theory of autopoiesis (that is, life is generated by itself) and its relationship to religion. When the excerpt was published in 1878 as a criticism of this theory and the scholars who adopted it, the debate about it began in the Arab world, and this discussion was linked to the scientific debates that took place in Europe. The editors of the excerpt, Sarrouf and Nimr, were Protestants and former teachers at the Syrian Protestant College. Despite their fundamental role in spreading Darwin’s ideas, they were among the most ardent haters and critics of the theory of autopoiesis in the Arab world for decades. They began to present various pieces of evidence arguing that creation occurred by the will of the Creator. As Elshakry states, “they worked to present narratives of emergence and evolution and other scientific results in a manner that supports their religious visions and the visions of their American missionary supporters.” This criticism by Sarrouf and Nimr of the theory of autopoiesis was the reason for the entry of a former colleague of theirs at the Syrian College into the midst of these scientific debates, and it was the beginning of his long journey in defending science, namely Shibli Shumayyil, who is one of the most important figures around whom Elshakry’s book revolves. Here, the book presents Shumayyil’s journey and visions, and how Arab readers – through Shumayyil’s renunciation of science and materialism – came to know “a new materialist vision of the theory of emergence and evolution.”

But Sarrouf and Nimr are not the only party that Elshakry presents as an attempt to adapt the ideas of development to religion. Rather, she presents an attempt by a more important party at that time, which is Islamic reformism, and in particular its most active sheikh in this debate, namely Sheikh Muhammad Abduh.

Islamic Reformism and Darwinism

Through the entirety of her book, Elshakry places two basic factors for Islamic reformism to enter the line of discussion about Darwinism. First is the activity of Christian missionaries who established schools and colleges and combined the dissemination of modern sciences with the teaching of Christian doctrines. Among their hectic scientific activity came the pioneers of spreading the theory of evolution in the Arab world. The editors of Al-Muqtataf and Shibli Shumayyil are all graduates of the Syrian Protestant College first and then its teachers. This perspective provoked many Islamic reformers at that time. They stood up against missionary activity that used science to promote itself among the children of Christians and Muslims alike. In response, the reformers began establishing schools for Muslim children. They worked to incorporate new methods and modern study topics into educational curricula. This was an incentive to harmonize religious texts with the modern science that was gaining overwhelming influence on the minds of learners. Chief among these efforts was the harmonization of religious texts with the theory of evolution.

The second factor in this intrusion into the debate over Darwin’s ideas was the response to the materialist ideas that included the theory of evolution and began to spread at the hands of Shumayyil and others. Here the author expands on two basic responses to Shumayyil’s materialism. One of them was published in 1888 by a Sufi sheikh, who was unknown at the time, Sheikh Husayn al-Jisr. His message was in defense of Islam against contemporary materialistic arguments. This message gained its importance from the spread of its readers throughout the Arab countries. The other response, and the most important one, was Muhammad Abduh’s translation of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani’s book entitled The Response to the Modernists. Here, Elshakry explains the context of al-Afghani’s writing of this response, which was not mainly aimed at Shumayyil, but rather the Indian thinker Sayyid Ahmad Khan. However, Muhammad Abduh and other Arab critics of Shumayyil found in Al-Afghani’s responses compelling arguments to confront the materialism rampant in the Arab world.

In the chapter on Sheikh Muhammad Abduh and Islamic reformism, before the author engages in verbal debate with evolutionary materialism, she refers to the sheikh’s rhetorical relationship with modern evolutionary thought. He called for the introduction of modern sciences into the curricula of scholars, and his talk about Darwin and the theory of evolution was generally full of positivity, but he did not pay attention in beginning of the twentieth century for those who accused Darwin of disbelief and spreading destructive materialistic ideas, as Al-Afghani did before him. However, Abduh did not elaborate on the theory of evolution in his repeated references to it. Rather, the author says that it is possible that Abduh – and also Al-Afghani – never read the works of Darwin himself. This aspect is one of the most important things this book sheds light on. How Abduh interpreted Darwin’s ideas in this approach demonstrates the paths taken by modern evolutionary ideas to reach broader theological discussions in Arab countries, which is what the book aimed to track. On the other hand, the author points out that the whole point for Sheikh Muhammad Abduh lies in the social meanings that one can derive from Darwin’s theory of evolution. Evolution, in the first place, is a process of “collective evolution,” and this transition with the theory of evolution to the “norms of societies” and their development is easily compatible with the inherited traditions in Islamic thought, especially with Ibn Khaldun. Also, this transition indicates an aspect in the pattern of the Arabs’ reception of Darwin’s ideas, an aspect that this work focused a lot on, which is the transition of his theory to social, political, and educational aspects. In this context, Aziz Al-Azmeh points out that Islamic reformism’s reclamation of Social Darwinism was conditional on the concepts of Social Darwinism, and if the discourse took the form of commenting on Qur’anic verses, then those verses were only occasions to link a definite Western intellectual reference to a symbolic reference, which is Islam represented by the Qur’an. This is what the author should have discussed, about the link between Islamic reformism between religious texts and Darwin’s ideas.

Later, as the author explains, the tinging of evolutionary thought in the Arab countries with radical materialism led to the mobilization of Islamic reformism to defend religion, by focusing on the compatibility of science and reason with Islam, and it became inevitable that a new theology would be mobilized, defending the existence of Allah and the Islamic faith with rational proofs. Which attempts to accommodate modern theories and discoveries. This matter is a basic result of this thesis, which is the emergence of the new science of theology, as a result of Islamic reformers’ confrontation with new scientific theories. Although we do not give this result the character of novelty, as some scholars of the Arab Awakening period have previously pointed to it. However, there is another more important result of this transformation that the author points out, which is the reconceptualization of the concept of Islam itself. For the first time, Muslim speakers began to talk about Islam as a type of civilization, in response to those who disparaged Islam in its support of science and civilization, and this is “the context in which efforts to attribute scientific ideas to Islamic civilization came with powerful rhetorical force,” as Elshakry says.

Conclusion

In the overall view of this work, we find a wide-ranging and resource-rich research effort. This research was able to add important results about the methods of receiving modern science in Arab countries from the mid-nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century. However, work of this kind should be cumulative. It should discuss the most important of the previous works that covered its topics during that period. Additionally, it should avoid too much narration that might prejudice the giving of each historical factor its appropriate level of emphasis.

Regarding the Arabic edition, the publishing house deserves praise for its selection of this serious work, noting that the deletion of the bibliography and indexes originally installed from the Arabic edition greatly reduced the amount of benefit from the work in this edition, and we hope to amend this in future editions.

T1619