The Sufferance

In that exact moment, all the patient wished for was sunglasses with bigger frames to hide the bruise under her left eye. Everyone sitting in the psychiatric clinic’s waiting room was carrying their suffering in cautious silence, except for her; her suffering made itself visible on her face, screaming, and shouting to the whole world: I am abused!

The nurse called out her name, so she walked to the doctor’s room with heavy footsteps, dreading the question she would surely face regarding the bruise. Then, she took a seat, her glasses remaining on her face.

The doctor began by asking about the patient’s response to the treatment after increasing the dose in the previous visit.

She shrugged her shoulders and said: “It helps me sleep.”

He tried to make her elaborate: “What about your mood?”

– “Hasn’t changed.”

– “And the thoughts you’ve been having?”

– “Haven’t changed either.”

– “Has there been any improvement since the last visit?”

– “Nothing’s changed, except for my sleep and my weight,” she paused for a moment then continued in a disgruntled tone, “and I don’t think that weight gain is something I could count as an improvement.”

In such situations, the therapist is faced with the impending pressures to diagnose and treat the patient’s symptoms: the pressure that the patient is feeling, the pressure of her family, and even the pressure coming from her workplace; everyone is waiting for him to end his sessions with some newfound explanation to what she is going through. What is the patient experiencing? Why hasn’t her condition improved despite her commitment to the treatment plan?

Here, the therapist finds himself in a challenge, something akin to a game of Tetris: the cubes are falling quickly, and you must ‘cram’ them into the most appropriate spaces. The disease symptoms awaiting an immediate diagnosis are represented by the falling cubes. Considering the limited diagnostic tools, and the gaps between each visit, “depression” emerges as a void far from ideal, but it is the closest space to cram these symptoms into. So, the doctor drops all the cubes into the depression space, treating them as depression. However, her condition is not improving, and as her complaints worsen, he feels that he must do something – which makes him try to intensify the use of the limited tools available. He resorts to prescribing different medications or changing the therapy sessions. And since the first cube was misplaced, the rest of the cubes pile on top of it inappropriately.

An Incapability

The doctor leaned forward in an attempt to encourage her to speak: “You can tell me everything.” He pointed to the sunglasses and continued, “We are here to help you.”

The patient hesitated before taking her glasses off to reveal the bruise that extended from right under her eyebrow to the top of her cheekbone, and then she tried to justify it. “He wasn’t in his right mind.”

The doctor inquired: “Have you talked to him regarding therapy…?”

She interrupted him, clearly agitated: “He’s against the idea.”

He asked her again, as if he did not believe her the first time. “Have you talked to him?”

Silence clouded over the clinic room, growing heavier by the second.

The doctor shook his head: “So, you have not talked to him.”

At that moment, the patient blew up at him: “Well, tell me what happens next?! How will you help me when the news of his addiction spreads in the family? In my children’s schools? For everyone who thinks of being associated with someone in my family?”

To lessen the severity of the situation, the doctor replied calmly, making his professional obligation clear: “You know that it is my duty; do you know that I have an obligation to report that you are being abused?”

She was on the verge of tears, but she held back for a moment: “My job is threatened by my health condition, which does not seem to be improving anytime soon. Our financial status has deteriorated after he was fired from his job because of his problems. All I have left is my family.” She tried to convince the doctor, “I won’t be able to live if I hurt them.”

Anyone who follows the field of Social Work will find that it emerged in Western Europe and America, post-World War II, and from there it spread to the world. Despite its development over the years, this field has not yet shed its “Euro-American” influence. When we talk about importing a field specialized in social work, we talk about high and sensitive contact with society and its concepts and values. The principles of social work were then influenced by a culture that is based on the value of the individual as an independent and unique being. These were to be applied, as they were, to completely different societies that were based on the family and community, and prioritize the interest of the group over the individual (talking about the Arab experience.)

Independence in Western culture corresponds to solidarity in Arab or Islamic culture, self-realization versus achieving the public interest, and strengthening individual identity in all its diversity and differences against a single common identity, and the list goes on. When employing social understanding – in its aforementioned form – in psychological practice, we will encounter another problem, which is its inability to accurately comprehend special cultural concepts that strongly intersect with psychological disorders. How can we understand the impact of topics with high cultural and social specificity without placing them in their own local context?

The Problem

The doctor stared at his screen, thinking how he could help her: “What about cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)?”

She shrugged and said: “I attended all the sessions and did everything I was told, but-” she trailed off, and the silence was louder than words could speak.

He sighed: “Well, in that case, all I can do is raise your dosage to two pills instead of one. What do you think?”

Her voice was barely above a whisper: “Okay.”

He wrote down the prescription then passed it over to her with a smile. He then wished her well. She put on her sunglasses, and as she was leaving, she stopped at the door for a moment, looked at the prescription in her hand, and then turned her gaze between the pharmacy and the exit door.

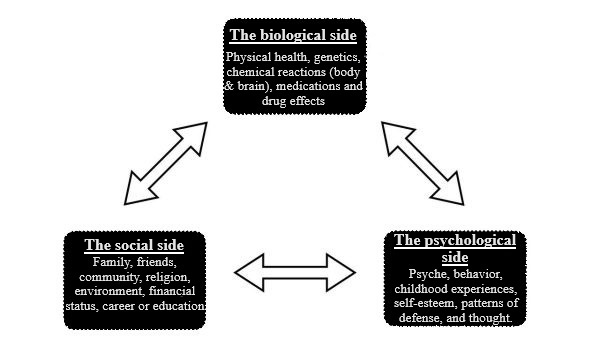

In the sixties, the American Psychiatrist George L. Engel brought forward the Biopsychosocial Model, which revolutionized the concept of the emergence and treatment of biological and psychological diseases. This concept evolved with other concepts, such as the patient-centered approach, as part of a movement to deepen the medical understanding of human illness and consider the individual differences that make each suffering its own form. The patient’s complaint is understood as a product of the interactions of the three sides of the model, and comprehensive treatment should include balanced activation of all these sides. To this day, this model occupies a central position in medical education in general and psychiatric education in particular.

This model, then, began as an attempt to transcend the dominance of the medical, biological, or material understanding of human suffering. However, more than three decades after its appearance, Steven Scharfstein, president of the American Psychiatric Association at the time, stated that psychiatrists allowed the previous model to be transformed into “biological-biological-biological” referring to ignoring the psychological practice of the other two sides. This statement coincided with the steady increase in the study and use of psychiatric drugs at the time.

Today, two more decades after this statement, the rapid reading of the therapeutic recommendations of most of the psychiatric disorders – especially the most common ones, such as anxiety and depression – reveals that most of the recommendations propose medical and psychological treatments, such as serotonin reabsorbing inhibitors, and cognitive behavioral therapy, for example.

When we compare Steven Scharfstein, and modern-day treatment recommendations side by side, along with the model depicted above; we will certainly spot an acute tilt in one of the sides of the triangle.

The Social Side: An Unfair Race

Unlike the other sides in the triangular model, which can be generalized, understanding and employing the social aspect requires knowledge of the fragmented nature of cultural concepts that differ from one society to another. The influence of the family system, the extended family, religion, customs and traditions, local spiritual beliefs (such as evil eye, jinn, sorcery), and others, are concepts characterized by a high degree of complexity and specificity. It is difficult to come up with recommendations that can be generalized without numerous and controlled studies of the impact of these variables on mental health. These variables, whether at the level of diagnosis or treatment – as opposed to biological or psychological ones – have not received their sufficient share of research and scrutiny, globally and locally. As a result, workers in the field find themselves in critical situations when faced with a dilemma dominated by the social dimension. In the face of the limited tools available, the therapist may find himself having to recycle his tools – such as medications and sessions – and this is what happened in the scenario mentioned at the beginning.

The dilemma of a society’s “cultural specificity” may be a trap for the practitioner who is unable to grasp the social context that draws the boundaries between what is disorder and what is a blatant image of a common cultural idea. An example of this is the difference between psychosis in the delusion of persecution on the one hand, and sorcery or the evil eye on the other. This may result in misdiagnosis and an inappropriate treatment plan with unavoidable consequences.

In her paper, the professor of social and cultural diversity Sarah A. Crabtree addressed the difficulties of teaching social work in the United Arab Emirates. Among other things, it is difficult for social workers in Arab countries to deal with cases of violence, sexual abuse, and child harassment, even when they are supported by the necessary theoretical foundation. On this basis, the specialist must report cases of violence. But in a society where all the joints are connected to the family – in which the head may be the abuser – and where the concepts of honor, reputation and shame are significant, specialists may be reluctant to report – even though the system obliges them to do so unless the patient refrains.

The professor —Sarah A. Crabtree— pointed out that specialists may feel helpless and hesitant about these cases, or they may strive to try to solve them within the family, considering their sensitivity. This is due to their belief that by doing this, they are protecting the family. This unfortunately cannot be commensurate with the nature and seriousness of violence and abuse, especially on children. In the same paper, Sarah points out that social work teaching, as she saw it, provides the learner with accurate skills, but in isolation from their social context.

Similarly, Munira Almasoud researched occupational difficulties facing family therapists in family awareness centers and societies in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, who, according to their definition in the study, perform some of the tasks of a social worker. Among the difficulties that were observed among the sample, which numbered more than 100 counselors, were: the lack of theoretical preparation and its separation from real practice, the weakness of the therapist’s culture with the values and customs of society, the scarcity of research and training opportunities, and the lack of clarity in the role of the therapist.

One of the difficulties that a mental health specialist may face in societies where the family occupies a central place is its impact on the individual’s decisions and course of treatment. In these societies, the individual is seen as an extension of the family, not as a separate being. Considering the widespread stigma towards mental illness, it is possible that the patient will face opposition from his family to receive psychiatric treatment, as they believe that he/she does not have the right to decide to receive diagnosis or psychotherapy all by themselves “alone,” because such a decision does not affect them alone. This not only affects the patient’s chances of receiving treatment but also violates his/her privacy and independence. This is equal to family members (father, spouse, etc.) trying to obtain information about a patient’s condition without his/her permission – information they are unentitled to reach according to regulations – which would cause ethical and professional dilemmas to psychological practitioners.

Therefore, there is a gap in the social aspect of psychological practice, transcending theoretical and practical levels. This gap not only ignores the social and cultural aspects that affect mental health; it also neglects the elements of community power that can be invested in mental health by studying and stimulating it. These elements are most notable, for example, in the protection against suicide, which Islam may provide to religious people, or in the family’s role and social solidarity with needy groups (as in disorders that affect individual independence, such as dementia and intellectual disability). These values can make a significant difference at the level of individuals, society, and the health system.

The gap seen here puts the specialist at a crossroads:

- To ignore this aspect of the model – no matter how important it is – and rely on other aspects.

- To apply imported concepts, devoid of meanings and inconsistent with reality.

- To strive to fill this gap according to what they see as right. In the absence of clear lines, there is room for individual judgements that often translate the principles and beliefs of the therapist, not the patient. This opens the door to a dangerous minefield of possibilities for transgression, negligence, and even results which are counterproductive.

As a result of this equation of the theoretical and practical gap on the one hand, and individual judgements on the other; recent calls for psychology derived from an important local cultural resource have appeared on the scene: Islamic psychology. Would this solve the age-old ambiguous problem?

Islamic Psychology: Is it the Missing Piece that We Need?

One of the tips for a mental health trainee is not to interfere with the value or religious system of patients. How can we define “intervention” and determine its limits? Mostly, there are no clear answers. If this advice is taken absolutely, we will deal with the patient in isolation from one of the most essential elements of his/her cultural and human formation. This does not apply to mental disorders – which are behavior, thoughts and feelings that are difficult to penetrate without passing through their foundations– and even some physical disorders.

Ignoring these data not only undermines the interest of the patient and limits the understanding of his/her suffering, but also collides with a wall of scientific evidence on the usefulness of cultural or religious interventions in treating several mental illnesses. How can we practice “Logotherapy” or “Existential Therapy” without addressing these aspects? How can we ignore studies that have measured the effect of combining some Islamic concepts with traditional psychological treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapies, on certain mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and loss? Many of these studies have shown interesting positive effects, some of which were more effective than traditional treatments.

Religious and spiritual beliefs have a special ability to give their adherents a high degree of consolation and meaning. The suffering of the individual, when placed in a religious context, acquires a meaning that gives it a higher dimension. In the Islamic understanding, for example, suffering is matched by reward, forgiveness of sin, represented by noble values and unity with higher models of patience. One of the best examples here is depression that a religious patient living their last days may experience due to cancer. Calling here for a complete separation of spiritual and religious principles (such as belief in fate, life after death, and following higher religious models in dealing with affliction and disease) from psychological practice means robbing the therapeutic experience of a treasure trove of meanings that may improve the patient’s life and help him/her overcome his/her ordeal and existential predicament.

Therefore, do we really need an Islamic psychological practice, without which we would have deprived patients of its benefits?

We need to take a few steps back to scrutinize the scientific evidence behind these interventions. We will find that most studies are based on samples of religious patients, and these interventions are consistent with their religious systems initially. Studies in this area are still preliminary and need larger ones to produce clear recommendations. We can also find other studies that are based on special practices in other religions, such as Buddhism, Christianity, and others. For example, studies of devout Christians have shown that the Bible was more effective than medications in treating patients with suicidal thoughts or alcoholism. Moreover, there are many who find their own meaning outside of religion; this meaning gives them the existential impact needed to recover efficiently that may be comparable to religious-based therapy.

An example to consider is that the patient’s suffering stems from their inability to harmonize with their community. When discussing the social dimension, we are also concerned with understanding the impact of conflict that may result when a person lives in an environment with values contradicting his own. Dealing with these cases requires the ability to create a safe therapeutic environment in which the client can be freed from their fears and feelings of rejection and isolation. This requires a neutral therapist who prevents the patient from reproducing the same societal environment within the clinic. Let us imagine, for example, a client with religious ideas that are not consistent with the prevailing societal religiosity. What would the situation be like with a therapist with a declared value system? Will they abandon their therapeutic neutrality to take on the role of a preacher who knows right and wrong?

Dealing with practices that acquire a religious character is different from dealing with others. Little by little, these practices may be seen as an extension of religion and its untouchable sacredness; therefore, whoever criticizes or rejects it also rejects religion. The idea of it being “Islamic” itself is faceted, where we can ask, according to which Islamic school will the practice be? Will it refer to Islam based on the therapist’s principles or the patient?

What are the qualifications required for a therapist to be considered an Islamic therapist? How would he deal with non-religious as well as non-Muslim clients? After this science, can we start studying different psychological sciences that serve the adherents of other ideologies, such as Arab psychology, feminism? etc.? The last and most sensitive question is, what if the treatment fails? Will we have the courage to admit failure? Will it be seen as a failure of the “religious” therapist, the “religious” treatment, or the “religiosity” of the patient? In each case, how will this reflect on the patient?

There is nothing new about these attempts to think of psychological practices involving specific human groups. For example, there are attempts to customize practices for people of African descent. However, one of the problems of these practices is that they confine a person to a specific framework, and to intellectual and value systems that assume that he/she moves within their limits only. Are you African American? So, this is what your suffering looks like, and these are the techniques that should help you.

This does not necessarily address the “application” of the idea as much as the “generalizability” … so I ask again, do we need Islamic psychology?

The Straight Side of the Triangle: A Prevention of Wasting More Energy.

I believe that a therapist cannot provide a service without understanding the cultural and religious background of his patients and striving to employ them. In societies where religion is a big part of the culture, its impact cannot be ignored. Ignoring it may even reduce the patient’s chances of obtaining evidence-based treatment. For example, in the case of a patient suffering from depression, and religion is a main source of his direction in life, he may seek treatment from a religious therapist and a medical therapist. If each insists on providing exclusive and separate treatment, there would be no surprise when he opts for the first choice (the religious therapist). Considering the difficulty of controlling and monitoring non-clinical practices, it is common for the patient to be exposed to physical and psychological risks that may result from this.

Acknowledging the complexity of the human psyche requires recognition of the need to make a greater effort to understand and deal with it. This requires the therapist to realize that the system of concepts and values for each patient is unique, not necessarily homogeneous, so that this realization results in a customized treatment plan that considers the privacy of the patient biologically, psychologically, and socially. This ensures that a patient is not deprived of a treatment that combines cultural and religious concepts that can serve him, and that there is no single template that determines the form and treatment of his suffering simply because he belongs to a specific group.

Some may argue that it may be impossible for the therapist to familiarize himself with the cultural and societal aspects of his patients. It is possible. But the pleasure and fascination of psychological practice is that it opens to a vast space of diversity and richness. This is the secret of the human psyche, and the most resource that a psychologist can learn from is the richness that each case provides. Every effort to understand it is an investment in the therapist’s experiences and the patient’s mental health.

This does not mean that we expect the therapist to deal with every problem of a social nature; rather, he must realize that his patient’s interest may require that some of the ways to improve his life be outside the clinic’s walls. In the example of the depressed patient above, the specialist can understand the role of a religious therapist if the patient wishes to hire him, to take a more positive role in coordinating and even supervising the intervention provided outside the clinic. The benefits of this collaboration may include increasing the patient’s access to evidence-based treatment, strengthening the patient’s relationship with therapists who respect his cultural specificity, and achieving every possible gain from treatment inside and outside the clinic. This would ensure not exposing the patient to folk remedies that may pose a risk to his physical and mental wellbeing, as well as achieving the far-reaching impact that can result from collaborating with folk healers who are highly respected and trusted in the community. We can imagine a form of cooperation on their part with psychological specialists – for example, by referring cases that require treatment. The expected results of this collaboration have been examined in studies conducted across several cultures (see references 1-4).

Conclusion

We need a practice that invests in the strengths of the value and social system and seeks to overcome the obstacles that this system itself places on the path to recovery. To achieve this practice, we must integrate mental health approaches with local specificity-aware topics, and step-up research studies testing the influence of the social aspect and the degree to which its principles can be applied in treatment. It is our ethical and scientific duty to publish the findings of these studies, even if they show that the studied treatment method is ineffective.

Achieving this enhances the quality of service that cares for the human being and respects his privacy and uniqueness and does not see him as a copy of others by ignoring his own principles, which can contribute to improving his mental health. A practice with this understanding also saves us from many efforts that might isolate people and divide them into groups through which the idea of a reincarnated human being is reproduced.

Side Note

At its beginning, George L. Engel’s “Biological-psychological-social-cultural” model was made up of four sides rather than three! However, for the sake of simplicity, the fourth side was discarded, because it was implicitly included under the social aspect.

T1705