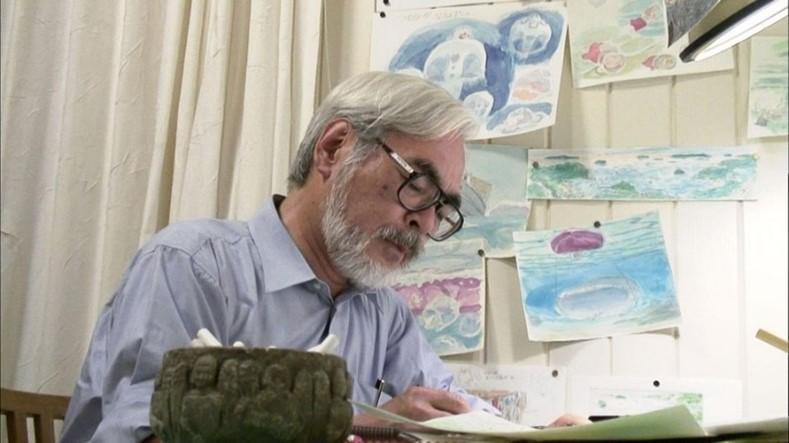

“The anime industry is about building imaginary worlds, and those worlds provide relief to the souls of those who are frustrated and tired of dealing with the harsh aspects of reality, and those for whom it is difficult to express their feelings clearly. I have sought to create anime works that immerse the viewer in feelings of lightness, purity, and renewal.” – Hayao Miyazaki

There are two types of building fictional worlds: “hard worldbuilding”, which is building a fictional world with an explanation of all the details and reality of the place and where the characters come from, and providing clear definitions and explanations of what this world contains, and another type, which is “soft worldbuilding”, which is what Miyazaki follows in most of his works. The knowledge presented about this imaginary world is not detailed knowledge, rather, we find that we are facing a world full of symbols and spaces that we must fill with our own understanding. We have no idea about the reality of this world, nor a clear explanation or presentation about the creatures in it. From a visual standpoint, his films are a work of art in themselves, as every scene is a painting filled with picturesque details and wonderful accuracy.

Regarding his stories, Miyazaki often touches upon the same themes, about nature and man and his influence on them, about childhood and the amazement of exploring the world, maturity and the passage of time, but he tends to lean towards symbolism, which makes every scene and every character bear infinite interpretations.

To clarify these themes, I will highlight some of his well-known works.

Spirited Away

The world in this film is the most complex world he has ever created, and it is the first Japanese anime film to win an Oscar. Chihiro mysteriously finds herself in a strange place resembling a world of spirits after her parents turned into pigs for unclear reasons. This world seems parallel to our world with only a thin barrier separating them, but we do not know its reality, nor the reality of these different and strange beings that blare and work all the time in every corner of this place, and although we do not find sufficient explanations, as the story progresses, we feel a kind of acceptance of all this strangeness without explanation or questioning. Perhaps this is the greatest advantage in building easy worlds, as creating a world like this does not make us question anything the writer puts before us or search for any logic in it. We may even come to the realization that its beauty lies in its remaining unexplained and in the fact that we do not know exactly what it is, and with the character’s acceptance of its fate and the other characters around it, we will have the same acceptance despite this chaos. We can deduce some clear meanings, for example, the time period that the film intends to display is a specific period of Japanese history, which is the industrial revolution in Japan, and perhaps the transformation of Chihiro’s parents into pigs is nothing but a symbol of the trait of greed and consumerism in which a person may lose themselves without paying attention in the midst of the consumerist world.

Looking at the entrance from which the story of Chihiro began, we find that it has changed as if a long time had passed between the beginning of the film and its end. It seems that the abandoned building collapsed or was demolished and was restored, then it was abandoned again. The trees grew tall, and plants covered the facade of the building. This place has been in place for a long time, and the heroine of the film realized this the moment she left. For her parents, it was a few minutes, but for Chihiro, it was several days, but exactly how long had it been? We do not know exactly, or whether it is related to the difference in the concept of time between the two worlds. There are many possibilities that we cannot enumerate, confirm, or deny.

But the More Accurate Question Is: On What Exactly Has Time Passed?

The most prominent aspect that any of us can notice in this film is its focus on the development of the character of Chihiro, as in the beginning she is a different character from the character we see at the end. Maturity is a fundamental pillar in the formation of this film. Her involvement in the world of labor alone, the transition from being a child thinking about moving to a new school, to her presence in a completely new “world,” and going through these different personalities and experiences that she would not have had willingly. A long time has passed between the person she was yesterday and the person she has become today. Doesn’t that feel familiar? Doesn’t life lead us towards maturity, only to look back and find that we have come a long way without realizing when we have come all this way?

In another context, the film also explores the theme of personal identity and self-discovery, a topic I’ll revisit later. Perhaps the clearest embodiment of this theme is No-Face. We see him in multiple scenes searching for meaning and a place to belong, even though he exists in a world teeming with different beings and fulfilling jobs. Yet, No-Face remains unfulfilled, unable to find his true place in this world. I find it a clear representation of the journey of self-discovery and the search for a meaning for one’s existence.

Howl’s Moving Castle

This work was adapted from the novel of the same name by the British writer Diana Wynne Jones. The first thing that caught my attention in this work was not the magical world, nor the moving castle animated by a speaking fire, nor the scarecrow trying to help, but the overwhelming feeling of familiarity.

All of these strange things and characters are completely familiar, as this world, with its strangeness, is presented as if it were a natural thing full of familiarity. The main character, Sophie, encounters many strange characters and events on her way, but she is not terrified by this strangeness, rather, her harmony and acceptance of various beings seeps into until we, in turn, stop wondering. I have always noticed this idea specifically in Miyazaki’s work: accepting the nature of things – even those incomprehensible things – as they are without being afraid of them. He believes that the nature of things is emptiness. By this, he does not mean a negative or unsatisfying emptiness, but rather an emptiness that can be filled with infinite possibilities. When we pin things down with rigid definitions and narrow concepts, we risk disappointment if reality doesn’t conform to our expectations. Instead, by embracing this emptiness, we open ourselves to the limitless potential of how things could unfold.

The film borrowed the idea of the magical world and the characters, but there are wide and clear differences between the film and the novel, especially with regard to the characters. Miyazaki tried to focus on the idea of “change” and external and internal transformations by presenting the characters in different forms throughout the film, starting with Sophie, who in the beginning of the film shows us a quiet young woman who spends most of her days working in a hat shop, and does not expect herself to have a different life or more exciting days. Sophie chooses the back roads even on her way back so that she does not mix with society or have to talk to anyone, until the Witch of the Waste’s spell is cast on her, turning her into an old woman. This transformation was not only external, in fact, Sophie’s personality changed completely, and she became more open and outgoing in life. More so, that spell that seemed like bad luck was the reason that made her go out to search for her own path and a destiny that she had never expected. Sophie changed and made a noticeable and striking change in Howl’s life, his castle, and everyone she met later. She was the one who did not think she had the ability to even change herself. We also see Howl as if he is going through several transformations, starting with “Howl with blond hair,” who seemed somewhat immersed in his conflicts with himself and the various aspects of his life that absorbed most of his energy, leading up to “Howl with black hair,” who seemed to have had the atmosphere of familiarity that filled the castle with Sophie’s presence in his soul.

The Relationship between Man and Nature: Princess Mononoke and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Traditional Japanese culture is closely and clearly linked to nature, man’s relationship with it and the role of this in helping him live a good life. Miyazaki presented a collection of his works to focus on this point and explain this relationship, which in reality is not based on clear foundations, as the relationship between man and nature in ancient times was based on harmony and unison, as man tried to understand nature and identify with it, and even derive his knowledge from it, aware that he was a part of it. In some way, nature was guiding man at that time, as he might move from one place to another in search of its resources to sustain life, and its cruelty might cost him his life.

In the films Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke, a type of conflict between man and nature is presented, and how such a conflict will not end with good results, and even victory in it will not be a victory because it will cost a high price and heavy losses in other aspects. Changes like these cannot be predicted or controlled, and their inevitability, despite their cruelty, may sometimes only signal the beginning of a new dawn. In both works, Miyazaki focuses on the idea that nature can restore its health without the need for human intervention, and this is shown to us symbolically in the plant that grows at the end of the film Nausicaä, and that man’s resistance to the inevitable changes of nature without trying to understand them is what has negative consequences for them, and thus for his life in them. In fact, those giant insects in the Valley of the Wind that seemed poisonous and destructive to man were nothing but an attempt by those creatures to cleanse its world and natural forests of toxins.

As for the movie Totoro, Miyazaki tried to alleviate the darkness and make a more cheerful movie. Although he presented works that reflected his pessimistic outlook, he stated in an interview that he did not want to convey his pessimism to people in his works, specifically to children, as he believes that the role of adults towards children is to protect their wonderful and optimistic perspective on life and the world. Despite the simplicity of the movie My Neighbor Totoro, it is the face of Studio Ghibli and one of the most famous figures in the world of anime. He presents his idea of the necessity of contributing to facilitating a path between childhood and the natural world away from modern technical distractions, and his belief in the importance of the child communicating with the natural and innate life around him, believing that this is the most valuable thing the child possesses, which is his unique and exploratory view of the world and things, and the unique ability to imagine and examine.

Loss and Longing

Miyazaki also presented in his works the theme of loss and longing. A sense of loss permeates many of his works – the loss of land, the loss of a friend, and even the loss of parts of one’s own self. These inevitable losses are a fundamental part of the nature of life. Most people who have seen his work, even just one piece, would agree on the overwhelming sense of nostalgia it evokes. This feeling is a vague longing, a yearning for something we cannot quite define. It might not be for anything real, but for imagined worlds and lives that resonate with us like forgotten memories, even though we cannot pinpoint their origin. As for loss, it may sometimes be nothing more than the loss of a childish perspective on the world, that amazement that cannot be regained, and although, according to him, he prefers to make films in which optimism prevails over pessimism, however, these feelings appeared on the surface in many scenes.

Porco Rosso, “Who Would Rather Be a Pig Than a Fascist”

In the context of loss, I bring up Miyazaki’s much more worthy film, Porco Rosso, which is clearly his most representative film of himself, his view of the world and humanity, and is aimed at older audiences. The film’s events take place in Italy in the volatile period between the two world wars. Porco was a fighter pilot in the Italian army who lost three of his friends during the war. He witnessed the death of many comrades and enemies, until he became disgusted with what the situation was like at that time. The film does not provide us with an explanation for the curse that befell him due to him becoming a “pig,” but we feel as if his disgust for humanity made him no longer prefer to be a part of it. Despite his pessimism, we discover that Porco holds optimism for the younger generation in improving the world and the human condition, and this is Miyazaki’s personal view, as he has always mentioned that he holds the future generations with hopes, and he wished they will not disappoint in improving the world. The film also focused on various topics that were prominent at that time, including the contribution of women to work and civilizational progress, and the importance of young minds. However, what was highlighted most was how a person does not go back to being himself before and after the war. Marco, the person, survived and did not lose his life as his companions had, but he lost a lot of himself, his “humanity,” and things that can never be restored, so he became what we see today.

Growth, Maturity, and Self-Discovery

From a psychological aspect, the complexity in his films is often psychological. The conflict is not between good and evil as much as it revolves around a person’s struggles with himself. In many of his films, the characters reach a point that can be likened to hitting rock bottom. It is as if complete despair surrounds the scene, absorbing all of its color and vibrancy. This collapse, however, is merely an indication of the major transformation that will occur in the character for the rest of the film. We witness characters move from a desire to disappear entirely, to integrating with and actively engaging in a strange new world. Others gather themselves up from the point of collapse, rearranging their circumstances in order to fundamentally change themselves. For example, Kiki initially thought that her path towards professional life and independence would be wonderful and full of enthusiasm and joy, but at a certain point her strength and motivation would fail, she would lose motivation and meaning, and this was the knot and the turning point in this seemingly simple work. In a conversation with Miyazaki, he stated that when he creates a work, he tries as much as possible not to create superheroes, but rather characters that resemble any ordinary human being. Chihiro’s journey in the film mirrors the five stages of grief. Initially, she’s cloaked in anger and denial. Remember the scene where she hides her face, muttering it’s all a bad dream? This is followed by a slump into depression, marked by long, sullen silences. But the final act brings a transformation. Chihiro throws herself into the thick of things, actively seeking a way back and even extending a helping hand to complete strangers in the spirit world. By the film’s end, Chihiro emerges a changed person – cheerful, brimming with a newfound energy.

In my contemplation of Chihiro’s path, I found that everything she went through is similar to our daily life. With a closer look, it is not as strange as it seems. In our lives, we will not always feel satisfied with the way things are going. There are paths in life that might not appeal to us – the unknown can be scary. But eventually, we have to face the truth: the only way forward is by embracing and enduring. Things rarely unfold exactly as planned, and the grand scheme of life, with all its causes and effects, is often beyond our grasp. Instead, we need to accept that control and complete understanding are illusions. Uncertainty and complexity are woven into the fabric of our human experience. Suffering is, unfortunately, just part of the deal – a lesson we all must learn.

T1673