Life as We Know it: A Narrative Introduction

“In the waiting room, I pondered my future, imagining it stable. I thought about the upcoming years and the projects and accomplishments they would offer, which helped me relax before the interview.” These words, used by my friend Mohammed to describe his job interview experience, do not just reflect his personal experience, but they also speak to the experience of an entire generation; the ambiguity of the future and the anxiety about the repercussions of important decisions are rooted fears amid the pressures of the modern age.

Mohammed was a creative writer that dreamed of turning his passion for writing into a career, separate from his academic specialization, so he could dedicate himself fully to it, live off its income, and achieve personal success. When one of the emerging companies specializing in content creation invited him for a job interview, his dream seemed to materialize before him in that room as he waited to be called in that morning.

“Mohammed,” the CEO of the company himself called out to him before warmly greeting him and leading him to the meeting room. The interview took on a conversational and friendly tone; one question followed another until the CEO reversed the roles, calling in numerous employees to sit facing Mohammed. Then, he ordered him to ask them any questions he had regarding working at the company. After several direct and concise questions and answers, the CEO sensed Mohammed’s satisfaction. He then gestured once again to the group of employees sitting across from him and said with a smile, “Well then, these are your new family members.”

The CEO suggested a temporary contract for Mohammed for several months, in order to allow all parties to evaluate their professional relationship before signing a permanent contract. Mohammed agreed without any complaints and began receiving projects immediately. However, his ambitions soon collided with the obstacles of the bureaucratic system, finding himself in situations where he was forced to compromise his creative vision, either to please the editor or the client. He continued to compromise until he felt he could no longer distinguish between his writings and those of his colleagues; there was nothing to tell these creative minds apart except for the accessories in their offices, their written output passed through the same editorial mill, producing packaged creativity under the guise of content creation and publishing.

“I overlooked all of this,” said Mohammed. “It’s a startup company operating on a successful profit model; who am I to go against that? Besides, I’m still at the beginning of my career, and I can’t do as I please at this stage. I spent my time there committed to the highest levels of professionalism, doing everything asked of me without ever saying no.” He paused for a moment, then continued with a disgusted tone, “But what I couldn’t stomach was the accumulated bitterness of unprofessionalism I faced until my last day at the company, as if the warm welcome was nothing but a false display by the management. You must understand, my friend, that this was my job despite being temporary; it was my only job, and as the end of the contract approached, I found myself crawling back into the unknown. At that moment, I was ready to compromise on anything because I was in desperate need of job security, of some semblance of certainty.”

During the beginning of his last week, Mohammed emailed the person responsible for his job contract, demanding a meeting to discuss his future at the company. However, the response didn’t come as he expected; it didn’t come at all. “The first, second, third, and fourth days passed, and there was no sign of this man because he was working elsewhere, and there was no way to reach him except through his email, from which I received nothing. I couldn’t sleep on Wednesday night, and I laid on the bed until dawn. Then, my device pinged, announcing the arrival of a new message in my inbox. I reached out and grabbed my device, and I opened it to see a reply from the man responsible for the contract. I smiled behind the bright screen of the device, holding on to what little hope I had left, but as soon as I read his message, I felt like I was drowning in darkness, burdened by my naivety.” He smiled bitterly and continued, “I thought he wrote his message at this time because he felt ashamed of his delayed response. I thought he would apologize and schedule a meeting for me that morning, but the truth was different.”

“He wrote his message without any introductions, apologies, or even the slightest hint of shame; all he said was that he would be on vacation starting from the end of the week, and I should wait for him to return from his trip.” Mohammed raised his hands in surrender and said with agony and pain, “Now let me tell you, my friend, I am not delusional about my position in life. I am not the center of this universe, and I don’t expect to always be present in people’s minds. So, I was fully prepared to overlook this treatment, but I simply couldn’t; the only thing that broke me in that message was its first line.” He pulled out his phone from his pocket and opened the mail app before handing it over to me. I looked at the screen and read what was written in the first line, “Hello Omar”! I looked up to find him beaten down from the memory and the feeling of alienation. At that moment, he uttered in a tone of sorrow I had never heard from him before: “It’s a Kafkaesque prophecy, and I am Gregor Samsa.”

What brought Mohammed to this level of sorrow is the work system that not only buried his creativity but also erased his identity. The man responsible for his job contract didn’t bother to confirm the identity of the person contacting him; to this administrator, Mohammed is Omar, and Omar is Mohammed, both representing the giant insect in Franz Kafka’s novel The Metamorphosis. This signifies that he holds no real value that entitles him to a special meeting to discuss his position. Moreover, he is not deserving to be Mohammed in that email; he is Omar, and he must wait until the responsible person returns from his trip to determine his future.

“This email bothered me, it bothered me a lot,” continued Mohammed. “It bothered me to the point where I felt ashamed of being bothered. I kept telling myself, ‘It’s just an email, don’t blow things out of proportion,’ but I couldn’t stop. I felt lost, unsure if burying my feelings and moving on was the right thing to do. So, I turned to therapy to help me understand and sort things out, but I left the clinic increasingly angry each time. The sessions revolved around my work failures, where, how, and why I failed, and what could be done to overcome these failures in the future. Initially, this seemed logical to me, but over time, it became apparent that the therapist was determined to blame me. Every incident that occurred, he viewed it from the perspective of my shortcomings, not the shortcomings of my superiors. There was only individual responsibility, nothing else, and he considered any attempt to hold management accountable an unconscious attempt to justify the laziness and slackness that our generation is characterized by!”

Mohammed shook his head and said, “But the absurdity didn’t stop there. After several weeks of leaving the company, I found out they had collaborated with this therapist to write content about the phenomenon of mental fragility. In his posts, he accused the youth of being unable to handle life’s responsibilities due to their weak willpower and excessive sense of entitlement. He then went on to outline his thoughts on the crisis of moral values among young generations and its direct correlation to their increasing mental disorders. All of this was under the banner of the company that caused my mental distress in the first place! It’s a real farce, my friend, because this blindness to the impact of one’s work environment is a significant factor that affects mental health. Once the environment is removed from the equation, only the individual remains to bear the full responsibility for their failures.” He paused for a moment and concluded his story by saying, “What a bleak outlook on life, unrealistic and unfair.”

After this detailed narrative introduction, it’s time to start our journey to answer the main question of this article: Are young generations struggling with a psychological fragility crisis, or is it a result of living in the modern world? This question leads us towards the book that introduced us to the concept of fragility in the Arab world, to examine its discourse, evaluate its objectivity, and ascertain its true goals.

Who are We Pointing Fingers to in the Discourse of Psychological Fragility?

In his controversial book Psychological Fragility: Why Have We Become Weaker and More Vulnerable to Breakdowns? Ismail Aref started his first chapter with a brief scene that paves the way for his analysis of the crisis of fragility among young generations:

“A young man falls in love with a girl, perhaps he saw her on social media, or maybe he noticed her on campus… The young man starts having feelings and his heart beats with admiration for her…”

Then he proceeded to outline various Hollywood scenarios for the happy beginning and subsequent deterioration of the emotional relationship, expressing with an air of inevitability:

“But after a while, whether it’s long or short, the young man discovers that he is living a fantasy…”

He then delved into describing the consequences of ending the relationship:

“The young man begins to spiral into a whirlpool of psychological problems… His life is negatively affected, he fails his exams, cuts ties with his friends, and withdraws into himself…”

He concludes his scenario by posing the question of psychological fragility and linking it to lack of accountability:

“Why do hearts break in this way and refuse to bear the consequences of their mistakes?”

Here, we must ask, who is this young man that the author constantly speaks of in various sections throughout the book? Simply put, he is a fictional character; he exists only in the mind of the author, making him susceptible to shaping according to the discourse’s objectives and orientations. This explains the author’s choice of the inevitable course of events. The author is the director, the one who controls every detail. According to him, every emotional relationship is necessarily corrupt, and its end is bleak, because this serves the author’s agenda in proving the charge of psychological fragility against young generations.

This does not mean in any way that the scenarios mentioned in the book do not occur in reality, but what we want to emphasize here, away from theorizing, is that the real events in our lives happen to real people living real lives that are not abstract or stripped from context, just like Mohammed.

To illustrate our point here, let’s rephrase a simple part of Mohammed’s story as if it were written in the abstract style of Ismail Arfa:

“A young man waits in the lobby of a startup company for a job interview. The CEO calls his name before warmly welcoming him.”

By comparing this with what Mohammed himself described, we can see the impact of abstraction in reducing his identity, feelings, and dreams, to superficial qualities. How would this reduction affect our stance towards Mohammed if we continued his story in the same style? Is it valid to analyze his behaviors and accuse him of fragility after stripping his story from its context?

No, it is not valid. Extracting an individual – whoever they may be – from the context of their lived experience turns them into something abstract (fictional and moldable), which negatively impacts the objectivity of the analysis. We cannot rely on the models presented by Ismail Arfa in his book for our analysis. Who knows, the young man falling in love with the girl may not have been allowed to marry her due to complexities of “social compatibility” in our Arab societies, but the abstract style of the fragility discourse deliberately ignores these details to create a childish image of young generations.

On this basis, objectivity in analysis requires a strict commitment to the context of real-life examples. This is where the details of Mohammed’s story come into play, playing a pivotal role in our understanding of the reality of psychological fragility.

Psychological Fragility Under the Microscope

Alright, then, let’s start from this basic idea: Mohammed’s life didn’t begin with the start of his story (in the company’s waiting room), and it didn’t end with its conclusion (after leaving the company). He lived a real life in the tangible world (starting from his birth and ending with his death), making it richer and more complex than can be squeezed into a narrative introduction. Therefore, we must begin by emphasizing the uniqueness of Mohammed’s life, as his beliefs, aspirations, relationships, shocks, and commitments, etc., are what make his life distinct from that of his peers; Mohammed is Mohammed and will never be Omar.

Mohammed paints a precise picture for us of the impact of the bureaucratic work system in creating feelings of alienation that plagued him throughout his time at the company (alienation from his written output and alienation from himself); he emphasizes in more than one instance his attempt to overcome it and his failure to do so:

“I overlooked all of this […] but what I couldn’t stomach was the accumulated bitterness of unprofessionalism I faced until my last day at the company.”

“I kept telling myself, ‘It’s just an email, don’t blow things out of proportion,’ but I couldn’t stop. I felt lost, unsure if burying my feelings and moving on was the right thing to do.”

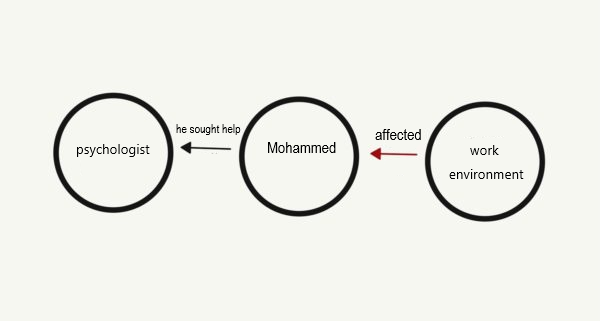

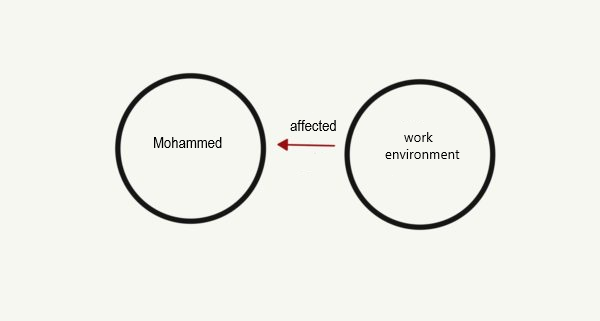

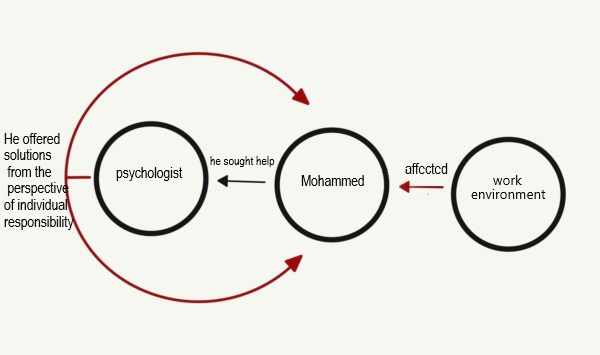

These internal conflicts, between his desire for self-realization and his need for job security, took a toll on Mohammed psychologically, to the point where he sought the help of a mental health specialist to understand what he was going through: Was the problem stemming from him personally or from the work environment?

Despite Mohammed’s openness to therapy and his willingness to accept the outcome, the psychologist’s insistence on placing the entire responsibility on him only increased his disturbance and discomfort:

“The sessions revolved around my work failures, where, how, and why I failed, and what could be done to overcome these failures in the future. Initially, this seemed logical to me, but over time, it became apparent that the therapist was determined to blame me. Every incident that occurred, he viewed it from the perspective of my shortcomings, not the shortcomings of my superiors. There was only individual responsibility, nothing else.”

Now, after completing the visual model, we can see the impact of individual responsibility in creating pressures that trap the individual between the hammer of the fragility discourse and the toxic work environment. Therefore, Mohammed’s suffering as a victim of this situation becomes evident:

“It’s a real farce, my friend, because this blindness to the impact of one’s work environment is a significant factor that affects mental health. Once the environment is removed from the equation, only the individual remains to bear the full responsibility for their failures.”

Is it Life or Psychological Fragility?

Here lies the fundamental problem with the individual responsibility narrative as adopted by the discourse of fragility. It isolates young generations from the influences of their environments (their communities, families, universities, schools, etc.), then demands that they bear the burdens of life on their shoulders. And when they falter, they are accused of weakness and laziness! This is because, from the perspective of individual responsibility, there is a solution to most of the problems individuals face in their lives, and these solutions often fall on the individual’s shoulders. There is no need for institutional efforts to address environmental problems because it is easier – and more profitable – to blame individuals and demand that they adapt to these problems themselves, even if their suffering is genuine.

- A teenager affected psychologically due to being bullied in their school environment is often accused of fragility and urged to toughen up and resist.

- A teenage girl impacted psychologically by abuse in her home environment is often accused of fragility and demanded to submit to her family’s will.

- A young man affected psychologically due to the lack of job opportunities in the job market is often accused of fragility and pressured to work any available job.

These are not imaginary examples we are trying to formulate to serve our narrative, but rather prevalent perceptions about the psychological fragility of young generations. Despite being unrealistic and unfair – as Mohammed stated and we clarified through the above model – there are people who believe in the validity of these judgments. They are the ones who confine the causes of psychological breakdowns to individual factors, aiming to relieve themselves from the burden of being held accountable. We hear them saying that the youth feel entitled until they become poisoned by this entitlement and more prone to breakage. They diagnose the crisis with symptoms revolving around fundamental aspects such as values, ethics, and goals, stigmatizing the entire generation with “inherent corruption” manifested in psychological fragility. This is what gave the discourse of fragility its preachy tone; it is based on comparison between generations. The older generation addresses the younger one and admonishes it, saying, “We are better than you. Our values are better, our ethics are better, and our goals are better.”

Let’s pause here for a moment and ask ourselves: What drives the discourse of fragility to adopt the individual responsibility narrative and the condescending preachy tone? By revisiting the ideas of those who have taken it upon themselves to promote this discourse, we can sense their underlying desire to preserve the social status quo and resist change. In other words, it is a socio-political stance opposing the need of young generations for change that keeps pace with the developments and challenges of the times. All of this is done in the name of “preserving social values”; because from a conservative perspective, change might be seen as the beginning of the erosion and disappearance of those values. Thus, we find those who reject even the simplest solutions to address the issues in the environment:

- By objecting to the enactment of laws that protect against bullying in schools, fearing it might dilute the standards of resilience.

- By objecting to the enactment of laws that protect against domestic violence, fearing it might lead to the breakdown of family bonds.

- By objecting to the enactment of laws that protect against workplace exploitation, fearing it might lead to a decrease in productivity.

In this case, it’s no wonder that there’s a widening gap in understanding between generations. What is the desired outcome of trivializing the suffering of young men and women? It’s a conflicting stance that reveals the detachment of the fragility discourse from lived reality, because life has never ceased to move through time. We live in a world that generates new challenges with every passing minute. The bullying experienced by parents fifty years ago is entirely different from today’s cyberbullying. Generations differ, suffering differs, and solutions also differ. This leads us to a crucial conclusion: the phenomenon of stagnation we are facing has emerged because of several factors related to modern lifestyle, absolving young generations from the charge of inherent fragility.

Indeed, to understand this phenomenon accurately and diagnose it effectively, we must examine ourselves as the children of this era.

Understanding the Young Generation

If we were to summarize everything we have discussed up to this point, we would say: Let’s think more broadly; let’s move beyond a singular psychological perspective and adopt a more comprehensive view with different analytical dimensions.

Now, let’s revisit the details of Mohammed’s story once again; his life decisions were not solely based on pure psychological desires but were also influenced by the hidden forces of his social and economic situation (Mohammed could not simply leave his field of study and pursue his passion without social and economic factors affecting this pivotal decision). From the initial sentences, he tells us: “In the waiting room, I pondered my future, imagining it stable.” What Mohammed wishes for is stability in all of life’s aspects. Is there a conceptual tool that provides a comprehensive perspective of these aspects? In other words, is there a tool capable of explaining Mohammed’s decisions and their impact on him without accusing him of fragility? Because the first and most important step for effective communication between generations relies on understanding – free from negative judgments.

For better or for worse, there is one concept capable of this task, and it is the concept of “identity.” So, how can we employ it as a tool to understand the younger generations?

The Encyclopedia of Basic Concepts in the Humanities and Philosophy tells us that there are two fundamental ideas to explain the concept of identity:

- The first idea, inspired by the works of Émile Durkheim, emphasizes that identity is shaped through socialization, by the collective values and systems that individuals acquire from society.

- The second idea, leaning towards the works of Max Weber, suggests that identity is the result of the paths of formation that individuals go through in their interactions with others.

Thus, in each identity, there is an “essential” aspect rooted in society and inherited during upbringing (according to the first idea):

- It encompasses the characteristics of identity passed on to the individual from the moment of genetic formation (in the womb), progressing through psychological, social, and cultural formation (among family members and society) in the early stages of life.

And there is a “creative” aspect characterized by the dynamic formed from various experiences and relationships (according to the second idea):

- It includes the characteristics of identity that the individual adopts – or rejects – through interacting with others and the world around them (a person may adopt a value not related to their society due to their openness to the world, or reject a value from their society because it does not align with their personal beliefs).

Let’s envision the matter as follows: When an individual is born into a society, they are given a chunk of original ideologies according to the cultural nuances of their local community (let’s assume it’s a chunk of marble in one society, in comparison to a chunk of wood or clay in others); this chunk represents their cultural bond to the community in which they grew up (as marble represents the essence of the marble community and what distinguishes it from other wood or clay communities). After a period of time, the individual – in their youth – is given the necessary tools to sculpt their own identity as they wish, to express themselves and their unique vision of life (to stand out in a homogeneous community of marble).

This concept may seem too idealistic and dreamy, as if it belongs to children’s storybooks; the community, families, and individuals live a happy life full of understanding. But we all know this is not true and it does not reflect reality, evident by the discourse of fragility that adopts a comparative approach between generations. Upon reexamining the details of the concept, we find that the disagreement lies in the extent of freedom given to shape the creative aspect of identity; it is restricted, not absolute. Meaning, society wants us to conform to certain patterns when shaping our identities; and here, the conflict begins in the issue of identity struggle between the individual and society.

Sufficient for Us is That Upon Which We Found our Peers

The conflict between individual desires and societal pressures is not unique to modern life; rather, it is an eternal struggle that parents have faced before, albeit in different socio-economic circumstances. They grew up in homogeneous societies where there was a prevailing perception of how life should be lived and what it should look like, which made them more inclined to compromise and accept ready-made stereotypes.

However, it is necessary here to put things in their proper context and understand that the psychological concepts we use to describe what is often referred to as “identity formation” and “self-actualization,” etc., are modern conceptual inventions that have gained their value from our contemporary lifestyle. Thus, they may not have held the same significance in the past. We can say that parents in the past may have aspired to achieve accomplishments, but did they aspire to achieve self-actualization in the same way their children do today? We cannot affirm that, because the term “identity crisis,” which describes the phenomenon of young people struggling with making life decisions, only emerged in the mid-20th century, indicating a link between the identity crisis and the technological and cultural advancements of the modern world.

This means that modern life introduced psychological, social, and economic pressures that directly impact the formation of the young generation’s identity. Their exposure to the world through the Internet has unveiled to them various options for living life, tipping the balance of identity towards the creative aspect. They now seek to break away from conventional molds and live their lives as they see fit, instead of conforming to societal expectations. Thus, they invest their effort in what they perceive as expressing their values and achieving their goals.

This is life as we know it today: open to all avenues and overflowing with choices to the point of paralysis. There are countless diverging paths with every step one takes, in a world laden with images that advertise the best path to a “successful” and “exceptional” life, prompting us to overthink every decision. Should I change my major? Should I leave my job? Should I insist on marrying the person I love? What should I wear? What should I watch? What should I say? All these available choices—or what we perceive to be choices—push us to obsess over making the largest number of correct decisions in the shortest possible time; there is no room for error, no room for hesitation!

And the result is crippling anxiety as we live and navigate through life. We do not suffer because we belong to a fragile generation incapable of bearing responsibility, but because we strive to live authentically in a fake world. Between the pressure from parents, peers, consumer culture, and targeted media, individuals ask themselves, “Is what I desire truly what I desire?”

Final Words from Mohammed:

After reviewing the draft of this article, Mohammed emphasized that I should add at the end that he is grateful for all the setbacks he faced in life, no matter how harsh they may have been on him. His failed romantic relationship left him broken, but it gave him the most beautiful days of his life, and his professional failure left him confused, but it won him wonderful friends.

Then he asked me to dedicate this article to everyone who navigates the journey of life with fear:

“May our setbacks illuminate the darkness of the path and reveal the truth of the world around us.”

T1694