My personal reading of Dante’s Inferno began when it reached its turn on my reading list. I approached it with a plethora of preconceptions, as is natural with any literary work. Oh, how cruel is Dante’s Inferno, for it shattered all my preconceived ideas. These preconceptions included the notion that Dante’s Inferno alone is the Divine Comedy, and vice versa. However, as I immersed myself in this particular section of the poem, I discovered a newfound appreciation. It became evident that these preconceptions had acted as a barrier, preventing me from fully grasping and savoring the poem’s overall momentum. I attribute this realization to Dante himself, as well as my own dedicated readings of his works. Interestingly, I have noticed a certain unexplained tendency, whether intentional or unintentional, among literary influencers on social media platforms. This tendency is preceded by the prominence of certain literary figures in popular culture and some writers. This tendency is marked by narrowing Dante the Poet and his Divine Comedy down, whenever they are mentioned, to Inferno alone, that it is Dante’s sole focus. I might even venture to say that Dante’s Inferno is better known than Dante’s Comedy, and I would not be far from hitting the mark. Yet, as a literature enthusiast, I assert that Inferno is not the entirety of The Comedy, and The Comedy is not solely Inferno. However, proving this assertion is not as straightforward as one might expect. It is more or less like affirming or refuting, in a literary sense, the Arabic origins of One Thousand and One Nights.

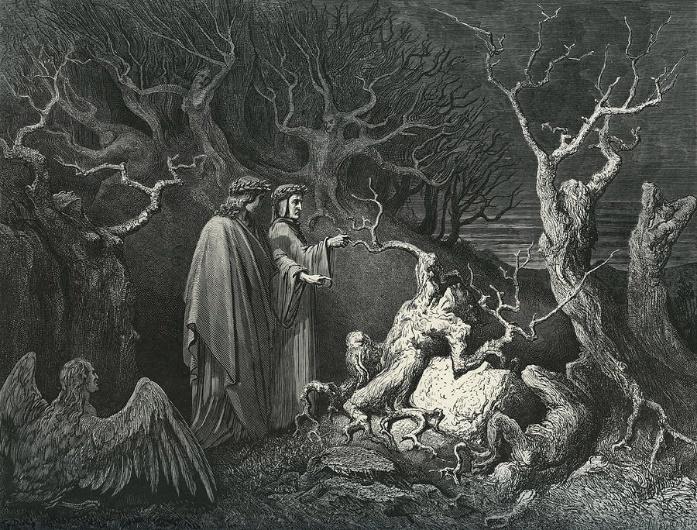

Dante embarks on his pilgrimage, initially filled with fear, terror, and trembling as he navigates through the shadows of the surrounding trees. Along the way, he encounters three monstrous figures and eventually joins forces with Virgil, taking his hand for a journey etched in history. Throughout his descent, Dante meets numerous historical figures and witnesses the divinely ordained kinds of torment, each meticulously matched to the sin committed. After a day and a half, the poets reach the depths of Hell, where they encounter Lucifer. They ascend from the depths, eventually reaching purgatory while gazing at the stars. Inferno concludes, and the reader’s journey with Dante comes to an end. The poem does not end, but the reading experience ends here. With the aid of Gustave Doré’s illustrations, the reader gains a deeper understanding of what the Divine Comedy conveys and what Inferno signifies. However, it is here that the erroneous assumption lies.

Dante’s influence extends far and wide in literature and culture. In some literary works, Inferno symbolizes insanity, a deteriorating psychological state, or a negative turn of events. From a logical standpoint, readers may argue that Inferno stands apart from the subsequent parts, leading them to skip the last two sections of the Divine Comedy. I did not realize this to be a problem until I started reading Purgatorio. In my limited readings of classical literature, film viewings, and even participation in online discussions and literary leaderboards, I have observed a recurring pattern where the focus is predominantly on Dante’s Inferno. This concentrated experience often leads to the perception that Inferno is the sole significant aspect of Dante’s work. Some translations solely focus on Inferno, as it is perceived to be the only part deemed worthy of translation. These readers do not necessarily prefer Inferno over the other two parts; rather, they disregard them entirely. While it may sound like an exaggeration, this is the reality. I was familiar with Inferno as a standalone work, unaware of its place within the larger narrative of the Comedy, never realizing it to be the third part of the latter.

Perhaps the allure of Inferno reflects our inherent human tendency to be drawn to the strange and the painful. As the “poet who visited hell,” Dante likely had a desire to narrate his story and convey the torment and fiery scenes he witnessed. He crafted this journey as a deliberate three-part narrative. Inferno, on its own, does not constitute a complete journey but rather an incomplete one, and limiting our understanding of Dante and the Comedy to this section offers an incomplete picture. If a reader views Inferno as a “mission” for learning, the pilgrim does not gain knowledge. If it is a “journey” for love, the beloved remains unseen. And if it is an “argument” for God, neither God nor His presence are ever witnessed. Continuation along this line of reasoning leads to the same conclusion: the journey through Inferno alone holds no ultimate resolution. Dante himself acknowledged the incompleteness of a journey confined solely to Inferno. We witness Dante attributing these words to Virgil in the first canto, foreshadowing the full journey: “I will guide you through an eternal realm, where you will hear the desperate cries […]. You will witness those who endure the flames, hoping to one day join the blessed company.” Virgil even acknowledges the limitations of his own guidance, stating, “If you desire to ascend further, […] there lies His world and His sublime throne. Fortunate is the one He chooses for such an honor.”

Finishing the first canto of Purgatorio, I vividly recall the moment Dante washes away the remnants of Inferno in the cleansing river. It felt like a breath of air after suffocating in the dense atmosphere of Inferno. The poetic style of Dante underwent a transformation from that of Inferno, becoming lighter, gentle, and more consistent and clearer in expression. As he remarks at the canto’s beginning, reflecting on the improved state of his pilgrim self: “Now, my mind’s vessel unfurls its sails, gliding upon tranquil waters, leaving behind the vast expanse of a profound sea. (…)” Dante had just set sail on his journey, signifying that Inferno was merely an integral part of Purgatorio, and Purgatorio, in turn, was an integral part of Paradiso. Dante traversed through both Inferno and Purgatorio with great enthusiasm, exploring the torments of souls in Inferno and their subsequent repentance in Purgatorio. This connection is evident from the very first two lines, where Dante contrasts his lost state in Inferno with the newfound hope in Purgatorio – a contrast absent in Paradiso. Some critics even perceive Purgatorio as an “extension” of Inferno.

Dante the poet demonstrates a remarkable effort to portray sins with their peculiar manifestations and colors, captivating us with his astute choices in depicting each sin. Giuseppe Mazzotta, an American professor specializing in Dante studies, asserts in one of his lectures, “Upon completing Inferno, you may believe that you comprehend Dante. If asked about the fate of those who commit suicide in Dante’s vision, you would likely answer that they become bloody trees. However, as soon as you begin with Purgatorio, you encounter its guardian and central figure, a suicidal pagan, leaving you utterly astonished. You begin to question why Dante crafted it this way. It is then that you truly begin to comprehend the Divine Comedy.” I experienced a similar revelation when I read about Cato receiving the two poets and choosing to guard the purgatory based on his steadfast principles, despite Dante’s opposing beliefs. It struck me that anyone who opposes Dante is destined for hell, a notion Dante refutes at the beginning of Purgatorio. In fact, throughout the Divine Comedy, even in Paradiso, we encounter numerous pagans.

Dante’s true understanding of descent and humility unfolds only in Purgatorio. He could not grasp the meaning of Inferno until experiencing the ascent through Purgatorio. Similarly, the significance of Purgatorio remained veiled until reaching Paradiso. As an example, Dante the Pilgrim weeps over the tormented souls in Inferno and occasionally faints, while Virgil repeatedly reminds him that it is God’s justice—a concept that Virgil himself does not believe in. However, in Purgatorio, Dante internalizes this lesson and delivers it directly to the reader, assuming the role of teacher once held by Virgil. He says, “And yet, reader, I do not want you to turn away from your good intention, by hearing how God wills to repay the debt.” Through this transformation, we witness a radical change in Dante’s character. He now recognizes that God’s justice transcends our emotions towards the torment of souls and the physical weight of their burdens. The torment and pain themselves are not of utmost importance; it is the outcome they yield, as Dante affirms. This change extends beyond this particular instance. We see Dante addressing the tormentors in a tone that may initially appear terrifying: “You arrogant Christians, you miserable wretches (…) do you not realize that we are nothing but worms (…)?” Where did the Dante who wept for them and could not bear to witness their suffering go? He did not vanish; rather, this is the fruit of his learning in Inferno, and it cannot be fully grasped by solely reading Inferno alone. Perhaps Franz Liszt’s musical composition, Dante, did not acknowledge the significance of the first two parts of the poem, and unfortunately, Wagner convinced him that no musician could capture the pleasures of Paradiso, resulting in no section dedicated to Paradiso. Nevertheless, Liszt’s music possesses its own poetic grandeur and enthusiasm, which demonstrates that Purgatorio is no less poetic than Inferno.

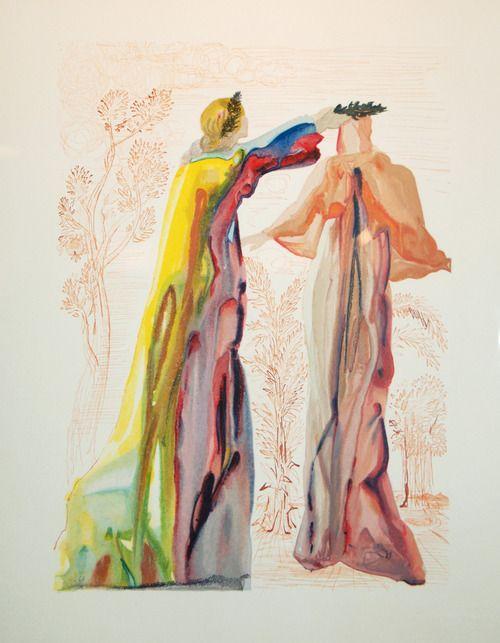

Some might justify the narrow focus on Inferno and the tendency to overlook the other parts of Dante’s journey, arguing that nothing surpasses the interest and creativity evoked when reading the vivid descriptions of the raging Inferno and its gates. They claim that there is no other poetic possibility as captivating as lines like “Abandon all hope, you who enter here” found in the other sections. I recall Dorothy Sayers, a renowned translator of the Comedy, stating, “If you want to understand the Comedy from reading Inferno alone, it is as if you want to understand Paris from its sewers.” While I do not endorse comparing Inferno to a sewer, Sayers captured something significant—the importance of Inferno within the broader context of the Divine Comedy, extending beyond its individual merits. Even if one were asked what they understood solely from reading Dante’s Inferno, they would struggle to provide a substantial answer, and this is not surprising. I remember the immense joy I felt when Virgil crowned Dante for achieving a “purely upright” will, placing laurel leaves upon his head and declaring, “Thus I crown you and wreath you.” as Beatrice takes on the role of guiding Dante the pilgrim. This scene is so exquisitely beautiful that Salvador Dali captured it on canvas, using colors that evoke the grandeur and poetic essence of this wreath ceremony.

Virgil crowns Dante with a crown of laurel leaves – Salvador DaliTo conclude this cautionary message, rather than focusing solely on Inferno, I urge you to embark on the complete odyssey of Dante’s Divine Comedy. To borrow Dante’s words from Paradiso, as he warns those who follow him: “Oh, you, who have been eagerly following in your boat, wanting to listen, as my ship sails along while singing. Turn back and look at your own shores once again. Do not tempt the deep waters, for if you lose sight of me, you might end up losing the way (…)”

T1628